Separating Exploration and Product in a Data Science Project

A Reddit comment

A few days ago, I read a post on Reddit about whether a data scientist should get a PhD or not. One particular reply in the comment section made me frown:

Lots of bad habits are learned in doctoral programs: writing unmaintainable code in scripting languages … and becoming accustomed to long lead times on projects.

I didn’t take this comment well, and I was triggered. I thought this person was biased against PhD programs and was over-generalizing. When I started on a snarky response, however, the thought sank in, and I saw that I might have been a victim of said bad habits.

It has been six months into my first job. The codebase in my project grew every day and had become less and less maintainable. The project folder was full of SQL queries and Python scripts. On the one hand, the model seemed to perform better and better, but on the other hand, it took longer and longer to run the whole process to get the result. I started to get a feeling that I would never see the finish line for this project.

Back in Nashville, I hung out with a few software developers. In software development, there were several common project management methods and principles that were results of years of experiments in the industry. One example is Agile. But in the data science world, I had not been able to find a principle to follow. So, I took on my work project the same way I took on my graduate school project — try some stuff, then try some more stuff, then try even more stuff. The pace was slow in graduate school, and I could be trying new stuff all day and still got away with it. The same approach created a problem in business. I knew something was missing in the way I manage my project, but I didn’t know how to address or solve this problem.

Then one day, I came across a blog post by @edwin_thoen. It clicked.

Two stages of a data science project

In his post A two-stage workflow for data science projects, Thoen described how he divided his workflow into the exploratory stage and the product stage. I recommend reading his post and check out his definitions of the two stages. The way I see the two stages are:

-

Exploration stage — Defining a business problem, finding data, understanding data, writing ad-hoc SQL queries, trying out different models. Everything happened in exploration is for my own or for my team’s use. The cost of reproducing results is high.

-

Product stage — Turning the insights learned in the exploration stage into an application/a report for business users. Everything in the product stage is stable and ready to serve anyone that requests it. The cost of reproducing results is low.

Separating the workflow in this way made a lot of sense when checked against my own experience, even outside data science. Here are two examples.

Example 1: as a grad student

When I was doing mathematical research in graduate school, I started a project by defining a problem to solve. Whether I could actually solve the problem or not didn’t matter at this point. What matters was that I had a general direction of my goal. It meant that I could break the big problem down into smaller chunks, and reduce the scope of the problem to a bite-size mini project that I could work on. Therefore, my workflow looked like this:

- Working on the bite-size problem

- Looking for a slightly bigger problem in the direction of my goal

- Working on the slightly bigger problem

- Repeat

I had solid steps for exploration, but the product was missing. In academia, the products were publications — a journal paper, a conference paper, or a book chapter. When I worked with my advisor, he encouraged me to write down in detail the process of each tiny problem that I solved along the way. At that time, I didn’t understand the rationale behind it. I did write things down, but only in a messy way. Thus, when I needed a publication, I had to go back and scramble together all my exploratory results. My work was not ready for publication.

Example 2: as a data scientist

A common situation at work went like this. There was my supervisor, A, and me working in my cube:

(A walks by cube)

A: Hey Chang, how’s the project?

Me: Good! We’re hitting x% accuracy this week, and I’m working on so-and-so next to see if I can get the model to x+y%.

A: What if we also try this and that? Do you think it’ll help?

Me: Yeah that might work, I’ll work on those next then.

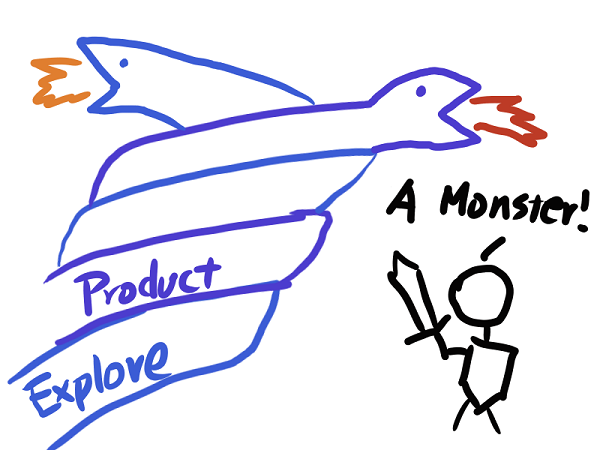

I had this kind of conversations with A several times a week. What I never realized was that the two questions were for different stages of a project. When A asked about the project, what A wanted to know was where I was on the product, and the idea A proposed for me to work on was about exploration. Because I didn’t understand this line between exploration and product, I was mixing up these two types of questions. As a result, the workflow of my project was mixed up, and the workload of managing this project became a monster that never stopped growing.

What I’ll do

When I had no idea about the difference between the two stages, I spent too much time in exploring, while my product was either too far from serving the business, or I didn’t have a product at all. It made me feel that I worked hard but produced little.

I think I can learn from car companies. The Civic that Honda put out in 2016 was probably different from the prototype car in the Honda lab — the engine on the mass production model was might be less efficient and less powerful when compared to the current prototype. But when it’s time to put out a new car, Honda took the parts that were ready and put together a product. The research was still going on in the lab, and would later become the basis for the Civic in 2017. The bottom line was that they put out a car and brought in steady revenue every year.

My problem at work was that

- my two workflows were interfering with each other, and

- I didn’t set a cadence for my product.

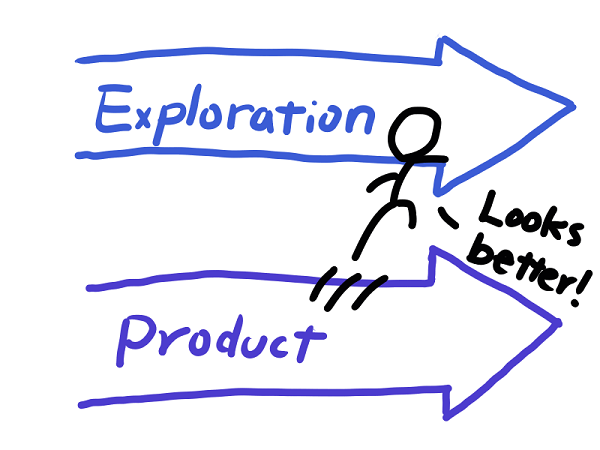

To address the first problem, I still don’t have a solid rule in separating my workflows, but I think I will need two backlogs — one for exploration and one for the product. Now, when my supervisor A comes with requests, I can sort the requests into respective backlogs without moving back and forth between workflows. If I am working on the product now, then I will not be completing items on the exploration backlog, and vice versa. By limiting myself to working on one and only one stage at a time, I can stay concentrated on current tasks and define better weekly goals for myself.

For the second problem, on setting a cadence for putting out products, I don’t have an answer yet. How much rigor should go into making the product? How can I leverage the exploration code into the production code? Those are things I am still learning. But now I have a framework to address and recognize my problems in project management.

If you have any comment or idea on this topic, please share with me!